- Home

- Diane Noble

Come, My Little Angel

Come, My Little Angel Read online

This is a work of fiction. The characters, incidents, and dialogues are products of the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

COME, MY LITTLE ANGEL

published by Multnomah Books

Published in association with the literary agency of Writer’s House.

© 2001 by Diane Noble

Published in the United States by WaterBrook Multnomah, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House Inc., New York.

MULTNOMAH and its mountain colophon are registered trademarks of Random House Inc.

Scripture quotations are from:

The Holy Bible, King James Version

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without prior written permission.

For information:

MULTNOMAH BOOKS

12265 Oracle Boulevard, Suite 200

Colorado Springs, CO 80921

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Noble, Diane, 1945–

Come, my little angel / by Diane Noble.

p. cm. eISBN: 978-0-307-78113-0

1. Sierra Nevada (Calif. and Nev.)–Fiction. I. Title.

PS3563.A3179765 C66 2001 813′.54–dc21 2001001644

v3.1

This book is lovingly dedicated to the memory of my father,

one of a handful of men who, nearly fifty years ago, built

Big Creek Community Church for their families.

This little church of my childhood—nestled in the pines

of California’s High Sierra—will always be my heart’s compass.

And to the memory of my childhood friend, Jeanie,

the real “Littlest Angel.”

Special thanks to my daughter, Amy Beth,

who at age four observed that angels

might be the real reason branches dance

when the wind blows.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Other Books by This Author

California’s Sierra Backcountry, 1912

DAISY JAMES BELIEVED in angels.

The morning the ten-year-old announced that she was certain angels lived in the pines around their clapboard cottage, her brothers Alfred and Grover, who thought themselves quite superior at ages thirteen and eleven, rolled their eyes. And her sisters—Clover, age eight, and Violet, five-going-on-six—giggled at such a notion.

With a heavy sigh Ma grabbed up baby Rosemary from her cradle by the fireplace and dropped her into the high chair in the kitchen, too busy and too tired to pay any mind to conversations about angels or anything else. Daisy could not help but hope her ma might listen this time, might give her a look that said she believed in angels too.

“I hear them whispering with the wind.” Daisy stepped closer to her ma so the others could not hear. “They smile down on people who walk underneath their branches.”

The baby blew oats with buzzing lips, and Ma scowled as she wiped her own nose and eyelids with the hem of her apron. “There’s no such thing, child,” she said to Daisy, paying attention at last. “Leastwise, not in this day and age. God helps folks that help themselves. That’s why He made you able and strong.” Her voice did not sound as harsh as the words did. “Able to do for yourself. Think for yourself.” She dabbed at the baby’s pink cheeks with her apron, and then added, “You can’t depend on magic. Or angels, either.”

Daisy circled a small lock of Rosie’s silken hair around one finger. “The Bible says that God’s angels watch over us always. He even tells them to keep us from dashing our feet against rocks and boulders.” She smiled. “I’ve always liked that last part. Seems to me His angels have to work extra hard in a place like Red Bud. That’s why I think they’re always nearby.”

“Humph.” Her mother poked another spoonful of oats into Rosie’s mouth.

Grover hooted. “They must not be payin’ God much mind. You’re always stubbin’ your barefoot toes in the summer.”

Daisy’s pa strode into the kitchen from the back of the house. His eyes crinkled at the edges as if he had been listening—and perhaps agreeing with Daisy. Just the sight of his worn, gray face turning bright for an instant warmed Daisy’s heart. “Daisy girl, why all these questions about angels?”

Daisy’s brothers and sisters were now crowding around the big oak table, talking and laughing while their pa served up bowls of oats and set them down with a clatter. Daisy didn’t want her family to know the secret she was hiding in her heart, so she clamped her lips together and settled into the bent wood chair between Violet and Clover.

“Daisy’th alway’th talkin’th ’bout angelth.” Violet, perched on a dogeared dictionary that rested permanently in her chair, held a spoon in her fist like a small tin flag. “Alwayth and alwayth.”

Clover snickered. At a warning glare from their father, Grover clapped his hand over his mouth. Even so, laughter spilled from behind his fingers.

“I suppose it’s because of all the folderol she’s hearing from Percival Taggart.” Ma was trying to coax another spoonful of oats through Rosie’s clamped lips. “If you ask me, he needs to stick to teaching music, not filling our children’s heads with such nonsense.”

Pa set the last bowl of oats on the table in front of Alfred. “Heard he walked the sawdust trail in a tent meeting. Last July, I believe it was.”

Violet waved her spoon. “Whath a thawdust trail?”

“Heard he gave up his whiskey,” thirteen-year-old Alfred said with a know-it-all look. “But everybody says it won’t last.”

Grover snickered this time. “Everybody knows it’s too late. I hear tell he owned the whole town before he drank it away.”

Alfred let out another hoot and leaned forward, his elbows on the table. “Folks say he once played the piany in Carnegie Hall before he came to Red Bud. Now he can barely finger a fiddle.”

Violet’s whine rose above the clamor. “Whath a thawdust trail?”

Pa looked past her to his sons, his forehead furrowed as deep as the river canyon out yonder. “We have a rule in this household…” He did not have to finish.

All the James children knew The Rule. No matter what else they might do or say, gossip among the children was forbidden.

Grover stared at his bowl, his ears turning red. Alfred took on a grumpy, bad-tempered look that seemed to appear daily of late. But Daisy sighed, feeling some better now that the attention was turned to someone besides herself.

Violet dropped her forehead to the thum side of her fist. Her spoon clattered to the linoleum floor. “But whath a thawdust trail?”

Clover squared her shoulders. “When someone gets religion, they walk down to the front of a tent. People all around them are singin’ and prayin’ whilst they walk in the sawdust.”

“I wanna walk in thawdust, then.” Violet took a clean spoon from her father and jammed it into her bowl of oats, stirring and playing instead of eating.

Pa sighed as he sat down on the far side of Alfred. “It’s a bit more complicated than that.”

“Mist

er Taggart said his heart is different now.” Daisy’s voice was low, and she stared intently at the small, painted rooster on the side of her bowl. She hoped Ma and Pa would not think of her words as gossip. “He said that only God can change a person’s heart.”

“It’s his throat that needs changing.” Grover loudly gulped a few swallows of orange juice for emphasis, followed by a loud “Aahhh.” Then he stopped short at the warning frown from Pa.

“Doeth Mister Taggart believe in angelth, too?” Violet’s eyes were wide.

Daisy looked up at her sister, then glanced around the table as seven pairs of eyes met hers. The only sound was a small chirping squeal Rosie made as she stuck her fingers in the oats.

Daisy bit her lip. “He says that God sends angels unawares.”

“What’s that mean?” Clover giggled. “Angels unawares.”

“It means nonsense.” Ma stood, her lips pressed together, and hurried to the sink. She lifted the hand pump up and down, almost like she was angry. Water dribbled out, and she dampened a cloth before heading back to the baby.

“It’s in the Bible. Hebrews, chapter 13.” Pa scooted his chair back from the big table. As soon as Ma finished wiping Rosie’s face, he lifted the baby from her high chair and propped her thickly diapered bottom on the crook of his arm. Rosie stuck her fingers in his mouth as he quoted, “ ‘Be not forgetful to entertain strangers; for thereby some have entertained angels unawares.’ ”

Daisy looked around the table as her brothers’ and sisters’ jaws dropped and their eyes grew round. Her heart thudded as she pondered her father’s words. Did he believe in angels?

But her ma spoke again before Daisy could give the astounding thought more pondering. “I don’t want our children growing up expecting angels or anybody else to rescue them from their troubles.” Ma wiped her hands on her apron, then turned to the table to speak to Daisy and her sisters. Her face looked tired and drawn, and her frail shoulders slumped. “Or expecting others to take over when they should be taking care of themselves.”

“I’ll wash the dishes, Ma,” Daisy said and rose from the table. “You go sit. Rest a spell.”

“Sit?” Ma’s laugh came out short and bitter as her eyes lit on the high stack of laundry at the end of the kitchen. “That’s a kindly thought. But truly, child, you should know by now there’s no such thing in a household such as this.”

“You girls help your ma now.” Pa’s worried gaze drifted from Ma to Clover and Violet. “You have enough time before school to help your ma turn the wringer. Skedaddle, now.”

Violet’s bottom lip protruded. “But I promithed Maudie Ruth I’d meet her on the playground. We wath gonna play double-Dutch jump rope.”

“Helping your mother is more important than jump rope.”

“But I’m not big enough to help. I thtill thit on a book to reach the table.”

Pa patted Violet’s strawberry blond curls. “If you’re strong enough for double-Dutch you’re plenty strong enough to hand your ma the laundry.”

“How come Alfred and Grover can’t do it?” Clover glared at her grinning brothers, who were still sitting at the table.

Before another word was uttered, chairs teetered, wooden legs scratched the linoleum, and the boys grabbed their belt-encircled books. In one swift movement, they hoisted the straps over their backs and hurried through the screen door. It closed twice with a bang.

“It’s not fair,” Clover muttered. She slumped to the far end of the kitchen, punctuating her departure with a slammed door of her own. Violet followed with a loud, exasperated huff. Soon their voices, not sounding the least bit put out now, mixed with the lower tones of Ma’s voice and could be heard from the small side yard.

Daisy filled the dishpan with water from the steaming kettle, sudsing it up with a bar of Fels Naptha soap as she added some cold water from the pump.

Pa still held Rosie, who was fussing now. He rocked her gently, patting her back between the shoulder blades as he leaned against the sink counter, his ankles crossed.

“You mustn’t think ill of your ma, Daisy girl. About not believing in your angels, I mean.”

“Do you, Pa? Believe, I mean?” She stared at the rising bubbles, not daring to look into his eyes for fear of being disappointed.

He didn’t answer right away. Only the sound of Rosie sucking on her two tiny fingers was heard in the big kitchen.

“Do you?” Daisy waited to breathe until he answered.

“There are many things about God, about His angels that we don’t understand. But just because we don’t understand them, it doesn’t mean they’re not true.”

Daisy turned to him and saw belief in his eyes. She almost dropped her favorite bowl with the painted rooster on the side. “You mean it?”

He smiled. “You mustn’t pay too much mind to your ma’s bitterness about things of God. She’s had sadness in her life and that’s made her afraid to believe.”

Daisy rinsed the rooster bowl and carefully set it on the counter. Though it was years ago, she remembered how Ma was before the baby died… how the house was once filled with singing and laughing. Was that what her pa meant?

On his shoulder, little Rosie closed her eyes and let out a big sigh that made her chest rise. Daisy’s heart filled with love for the little girl. How would she feel if Rosie were suddenly gone? A wave of sadness washed over her at the thought, and she bit her lip. If just the thought hurt this much, what must it have been like for Ma to have a baby die?

Just then the company whistle blew from across town. Pa shifted Rosie to one side, then pulled out his pocket watch. “It’s time to go,” he said. He strode to the old wooden cradle that sat near the fireplace and gently placed the baby inside.

Daisy’s pa was big, broad shouldered. She had always imagined Paul Bunyan could not be half as strong as her pa. But watching him tuck in the sleeping Rosie, then plant a kiss on her fuzzy head, made her wonder how a big, powerful man like her pa could hold a baby with such tenderness, his face all gentlelike.

“I’ll be late tonight,” she heard him say to Ma a few minutes later out in the yard. “There’s a meeting after work. Has to do with some blasting in tunnel number eight.”

“Orin, you’re not thinking of going in the tunnels again!” Ma sounded scared. “You told me you wouldn’t.”

Daisy stepped outside to the wide porch and looked toward the spot of brown grass near the wringer washer where they spoke. Violet and Clover had disappeared. They had most likely run off to the schoolhouse.

Daisy did not mean to eavesdrop, but the fear in her ma’s voice kept her rooted to the peeling boards on the porch.

“We need the money, Abigail,” her pa was saying. “There’s not enough to pay the mercantile bill again. It’s getting so that more goes out for food and such than I’m paid at the end of each week.”

“There’s got to be another way…” Ma’s voice dropped, and Daisy couldn’t hear the rest of her words.

“There’s more,” her pa said. “It’s about Alfred—”

Her ma brought her hand to her mouth. “You said you wouldn’t… you said you’d let him finish school. He’s only thirteen.”

“I know I did, but circumstances are dire, Abigail. Besides, he’s nearly fourteen. That’s what the meeting is about. Most of us have sons who can help make ends meet. We’re hoping the company will take them on. And lately his attitude, Abby, well, it’s downright defiant at times…” His voice lowered, and Daisy strained to hear.

“He’s so young,” her ma said slightly louder.

“I was working in the mines by age twelve,” Pa said. Then they turned their backs to her, and she could not hear any more. But the sad slope of their shoulders told Daisy more than any words could. Her pa wrapped one arm around her ma’s thin frame and drew her close. For an instant, her ma lay her head against Pa’s big chest. Then she stiffened and stood tall once more. Ma did not turn to wave when the company whistle blew again and Pa strode down the dirt

road beneath the pine tree branches.

As her ma cranked the washer handle, feeding the clothes through the double rollers of the wringer, Daisy raised her eyes to the stand of sugar pines that surrounded their bleak little shack of a house.

A slight wind blew against the dark green needles, making them sway and dance, just as they might if angels were walking among the branches.

Angels! She grinned. Even Papa agreed there might be such a thing. Think of it!

She giggled as she considered the secret she had been holding dear. A secret that might change all the families in Red Bud. Especially her own. The secret was as precious to her as the scent of rain on a dusty summer’s day. Only two people knew of it, besides herself, of course: her best friends Wren Morgan and Cady O’Leary.

Minutes later a rustling breeze kicked up her hair as she skipped along the path to the one-room schoolhouse. Shouts and laughter carried toward her as the children waited for Miss Penney to ring the school bell.

Before stepping through the rusty-hinged gate into the play yard, Daisy looked up into the canopy of pine branches. They danced and swayed and sang in the wind.

A treeful of angels, she thought with a grin. Imagine such a thing!

She just knew angels were around her today. This was the day she planned to tell Mister Taggart her secret. No matter what her ma or anyone else in Red Bud thought, without Mister Taggart her secret would not spring to life.

And if it did not, Daisy thought she surely might perish.

ABIGAIL JAMES WENT about her morning chores with a heavy heart, sweeping the kitchen floor, mending the elbows on Orin’s old jacket, and kneading the bread dough she had set out at dawn to rise.

Just after Abigail sewed the last patch on Grover’s trousers, Rosie began to fuss in her cradle. Abigail hurried inside, lifted the baby to her shoulder, and settled wearily into the old, scarred rocking chair near the fireplace. Rosie drank hungrily to the rhythm of the chair’s movement.

Abigail leaned back, feeling the first contentment of the morning. She trailed her fingers along the worn chair arms, touching the small grooves of teething marks, some more than a decade old. She wondered which marks belonged to Alfred, or Grover, or even sweet Daisy. The little ones, Violet and Clover, had chosen a stout lamp table to soothe their swollen gums as their teeth broke through. Their marks mixed with a design of wild roses that Orin had carved around the edges when he built the piece.

Angels Undercover

Angels Undercover The Sister Wife

The Sister Wife The Betrayal

The Betrayal The Missing Ingredient

The Missing Ingredient Come, My Little Angel

Come, My Little Angel The Butterfly Farm

The Butterfly Farm The Master’s Hand

The Master’s Hand Heart of Glass

Heart of Glass Through the Fire

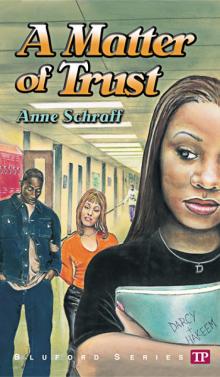

Through the Fire A Matter of Trust

A Matter of Trust The Veil

The Veil The Curious Case of the Missing Figurehead: A Novel (A Professor and Mrs. Littlefield Mystery)

The Curious Case of the Missing Figurehead: A Novel (A Professor and Mrs. Littlefield Mystery)