- Home

- Diane Noble

The Veil Page 11

The Veil Read online

Page 11

Lucas held up his hand to silence her. “Sophie! Don’t speak such blasphemy! Especially here.” His voice was stern.

Hannah considered the change in Lucas’s demeanor, the seriousness of his warning. Yet she knew something was troubling him, something more than just his leaving. When he glanced around as if assessing nearby listeners, she knew it was time to get her aunt inside. Hannah took Sophronia’s arm. “We need to go in. It’s time.”

Sophronia nodded reluctantly, and Lucas escorted them up the walkway then held the door open for the two women to enter. As she passed him, Hannah met his eyes. “Will I see you again before you go?” she whispered so no one standing nearby would hear.

“Of course,” he said gently.

“Tonight?”

In the foyer, Porter Roe spotted the couple and raised a hand, motioning for Lucas to join him. Lucas merely squeezed Hannah’s hand before moving toward Brother Roe.

Hannah settled beside Sophronia on a wooden bench in the long, bare room, facing the Prophet and his council, who sat on a platform in front.

The Saints lifted their voices in song then several of the elders prayed endless, droning prayers. Usually Hannah had to stifle several yawns to make it through the interminably lengthy services, but not today. Her mind whirled with Lucas’s news of his departure.

It wasn’t until the Prophet stood to speak that her attention was finally captured by the service. Some of the older leaders droned on with voices that Aunt Sophie often said were worse than the monotonous buzzing sound of a beehive, but Brigham Young was different. He spoke with a spirit of inner fire and strength, a voice that made people sit up and take notice. Hannah was fascinated by him.

She watched him move to the pulpit. A person couldn’t help being drawn to his presence. It wasn’t just because of his dark, ruggedly handsome face or his godly and majestic bearing. No, Hannah thought as she watched him, there was something else. It was as if he could see into a person and know all that was there. Hannah shuddered, dismissing the thought, and gave her attention to his words as he stepped back from the pulpit and stared out at the congregation, first to the men, then to the women, speaking fervently about the Saints’ responsibility to keep their covenant with God.

He had been speaking for nearly half an hour when his voice became angry, rising with emotion. “There is not a man or a woman who violates the covenants made with their God who will not be required to pay the debt,” he said, leaning on the pulpit.

Behind the Prophet, the elders kept benign gazes on two people—first a man, then a woman. Hannah glanced at the man who had caught their attention, sitting on a bench across the room. She thought she remembered his name was Hambelton. His head was down as if embarrassed.

The woman, sitting on the bench in front of her, was the pretty wife of Brother Brown, the storekeeper. Hannah wondered why these young people would have caught the attention of those on the platform.

There was a long silence in the room. Then the Prophet slammed his fist onto the pulpit. Several people jumped, startled.

“Let me say this again! There is not a man or a woman—not anyone—who violates the covenants made with God who will not be required to pay the debt. The blood of Christ will never wipe that out.

YOUR OWN BLOOD MUST ATONE FOR IT!”

The room was deadly silent as the speaker looked out across the congregation, his face fixed in rawboned judgment, his brows knit together. His voice remained loud. “There are sins that men commit for which they cannot receive forgiveness in this world or in that which is to come, and if they had their eyes open to see their true condition, they would be perfectly willing to have their blood spilt upon the ground.

“And furthermore, I know that there are transgressors who, if they could step outside of themselves and see that this is the only condition upon which they can obtain forgiveness, would beg of their brethren to shed their blood.” His eyes bored in on individual Saints, first one, then another, then another. Then he lowered his voice so it sounded almost gentle, tearful, when he continued, “I have had men come to me and offer their lives to atone for their sins.”

Hannah heard a few people draw in their breath. Then there was silence, and he went on, “It is true that the blood of the Son of God was shed for sins through the Fall. It was shed for those sins committed by men.” His gaze again traveled from face to face as if watching for reaction to his words. “There are sins that can be atoned for by an offering upon an altar, as in ancient days.”

He suddenly smiled, nodding as if he knew they were all in agreement on that point. A long silence followed, then his voice rose in righteous-sounding anger when he again spoke. “There are sins that the blood of a lamb or of a calf or of turtle doves cannot remit.

“If there is anything that separates you from your God, from your Church, it has to die,” he said. “And I read to you the words of the Holy Scripture: ‘If thy right eye offend thee, pluck it out, and cast it from thee: for it is profitable for thee that one of thy members should perish, and not that thy whole body should be cast into hell.’

“What is it in your life that offends God, offends the Church? Whatever, whoever, it is an abomination before him and must be plucked out and cast away.”

Hannah swallowed hard, thinking the speaker looked directly into her eyes as he spoke.

“And if you can’t do it,” he continued, his voice growing softer, “if you cant do it… those who love you will have to do it for you.”

Shivering, Hannah sensed someone watching her and glanced at the elders and apostles seated behind the speaker. John met her gaze. But there was something in his expression that alarmed her. Uncomfortable, she turned quickly away.

A few minutes later the sermon was over, and Hannah sighed in relief as they stood for a final hymn. Then she helped Sophronia move slowly down the center aisle toward the back of the church. Her aunt smiled and nodded to friends and neighbors as they passed, and when they reached the door, Hannah noticed that the apostles and a few of the elders now gathered around the Prophet. Lucas Knight, Porter Roe, and John Steele stood to one side, deep in conversation.

When the rest of the congregation had filed from the meetinghouse and the doors were closed, John Steele stepped to the pulpit. Several elders and apostles filled the first two benches, most of them active Danites. Lucas sat at the end of the second bench.

“You all realize why we’re here,” John Steele said solemnly.

There were murmurs and nods of agreement.

“Let’s get this done, then.” Steele nodded to an elder at the center of the first bench. “Bring in the accused.”

The elder entered a small room to the right of the podium, and after a few minutes came back with Brother Hambelton. The young man had the fresh-scrubbed look of someone who hadn’t known much of life. His cheeks were flushed red as he stood facing John Steele.

“Brother Hambelton, turn and face your accusers.” Steele then addressed his words to the council. “Brothers, we have one of our own who has violated his covenant with God. He has sinned.” The young man looked at the floor.

Steele went on. “But if we love Brother Hambelton, what should we do? What should he do? Think about the Prophet’s sermon. What does God require of him if he wants to be restored into fellowship with God? What does God require of us to save his eternal soul?”

The young accused man, his face now covered with perspiration, still stared at the floor, his shoulders slumped forward. Steele moved closer and circled his arm around the man’s shoulder. Brother Hambelton stared dead ahead as if transfixed.

John continued, his voice now a whisper, “Some sins must be atoned for by the blood of the man. Isn’t that what we heard today?” He sighed, giving the words time to soak in, then repeated, “The Prophet has said—and it was from God—that there is forgiveness only through the shed blood of the man himself.” The young man nodded, now looking at John as if in some silent agreement.

“What have you

to say, Brother Hambelton?”

The young man pulled out a handkerchief and mopped his forehead. His hands were shaking. He took a deep breath and tried to speak but only stammered, as if the words were stuck in his throat.

“What have you to say?” John Steele asked again.

“I, ah, I—” He mopped his face again, looked into his accuser’s eyes then toward the council members sitting before him. He took a deep breath. “I wish to die for my sins.”

“And what sins are these that you wish to die for? You must confess them—each and every one.”

The young man’s cheeks were still flushed, his eyes bright. He spoke in a murmur. “I confess the sin of adultery.”

Steele shook his head sadly at the younger man. “Adultery is a sin of weakness and depravity.” He didn’t speak for several minutes as he watched Brother Hambelton carefully. “Is it not true that after committing adultery once before, you were warned by the council—warned that death would be the penalty if you sinned in such a way again? Is this not true?”

Brother Hambelton nodded. “Yes,” he said.

“You sold your birthright for a mess of pottage. You sold your soul’s salvation for a few moments of carnal pleasure. You knew the consequences—yet you led the adulteress down the same evil path.” John looked at the man, his eyes hard. “What have you to say to this?”

“I know I sinned. But please accept my death as atonement for—” He hesitated. “—for us both. Don’t punish her. It was my doing. I am the sinner.”

“We are here to deal with your sins. Yours alone. How we deal with the adulteress is not your concern. Continue now with your confession.”

“I confess the sin of pride.”

“How so?”

“It was prideful thinking that I could have another mans wife.”

“What else?”

Brother Hambelton confessed his sins, one by one, large and small. Then in a clear voice he said he was pleased that the Church was taking a stand against sin—rooting it out before it could spread. Blood atonement was a powerful teaching. How else, but by blood, could a person be cleansed?

But Lucas, seated and watching the proceeding in horrified fascination, wondered how much bloodletting there would be before the reformation that Brigham Young spoke of was complete.

In a flash of remembrance, Lucas saw the old shed at Haun’s Mill. He remembered the terror, knowing they were surrounded by men who were trying to kill them. He saw his pa die from the first ball fired. Then the others had died one by one, until there was only Lucas lying facedown on the floor and his little brother, Eli, by his side.

He heard his brother’s screams as the Gentiles pulled him, kicking and fighting, from beside Lucas. “Nits make lice,” they said. The brutal words roared again in his head. “Nits make lice. Nits make lice.” He wanted to run to his baby brother, save him from the monsters. But Lucas couldn’t move. He lay flat on the floor, playing dead. Then he heard the screams of his brother calling out for help, calling him by name. Over and over again. He saw in vivid clarity the pink and red of the little boy’s head as the ball blew it to pieces. He could still hear his brother calling his name. Through all the years it had never stopped.

Lucas came back to the present as John Steele directed Brother Hambelton to kneel. The council members gathered around him and began to pray. John Steele stood with his hands resting on the bowed head of the young man. All the elders sank to their knees encircling him. They raised their arms above their heads, folding them at the elbows to form the shape of a square.

As Lucas knelt beside John Steele, the older man whispered, “You’ll be meeting us later tonight, son. It’s expected.”

Sick at heart, Lucas nodded mutely then listened as each of the apostles prayed for Brother Hambelton’s eternal soul.

Lucas knocked at the cottage door long after Sophronia had retired to her bedroom.

“I can’t stay,” Lucas said, stepping inside. He took both Hannah’s hands in his. “It will make it too difficult to leave if I stay longer.”

“You make your journey sound so final. You’re coming back, aren’t your

“Yes, of course.” But something about his expression seemed unsure, guarded. “When?”

“I’m not sure. It depends on the success of my work with the new converts. But I’m hoping it won’t be long.”

Hannah didn’t speak for a moment, just looked at him, already feeling the loneliness of missing him.

Lucas let go of her hands and touched her cheek lightly with the back of his fingers. “I’ll miss you, Hannah.”

She reached up and took his face in her hands, looking directly into his eyes. “I don’t want you to leave,” she murmured, her voice dropping to a whisper. “I know I’ve childishly asked you to marry me, told you how much I think we belong together, but I’ve never really told you all that’s in my soul. Those thoughts that only you would understand.”

The stark grief on Lucas’s face matched her heart’s deep sorrow. But it was a different kind of grief than her own. It was as if he knew something he wasn’t telling her. Lucas, seeming to sense her confusion, touched her lips with his fingers. “Don’t say anything more, Hannah. I’ve told you all I can.” Pulling her into his arms, he held her close. They stood in the center of Sophronia’s parlor, holding each other tightly. “I don’t know what I’ll do without you,” he whispered. Then he pulled back and considered her without speaking, as if memorizing her face.

It came to her suddenly. “Atonement,” Hannah suddenly said, thinking of the mornings sermon. “Am I the eye that offends you? You have to pluck my love from your life and cast it away?” She backed away from him, astonished at the clarity of the meaning of Lucas’s mission. “Is that why you’re leaving? Is John Steele asking you to give me up as some sign of your devotion to the Church?” She paused, narrowing her eyes as a new thought formed. “Has he asked for my hand in marriage—to test your devotion? To him? To the Church?” Her last words came out as a sob. “That’s why your goodbye sounds so final.”

“Hannah, no!” he began, but she interrupted.

“It’s the Church, isn’t it?” She let out a ragged sigh. “And to think this morning I realized I would not die for this—this—” She searched for the word. “—this damnable institution. I decided that you—you, Lucas Knight—you and our love for each other—would be the only thing I would die for. Not the Church or its gods. I may be condemned. I don’t care. No one can make me stop loving you.” Then she covered her face with her hands.

“Please, Hannah,” Lucas began again. He moved toward her and tried again to draw her to him.

She pushed him away. “Don’t say anything, Lucas. Just listen.” She turned to look at him. Tears trailed down her cheeks, and she swiped at them with her fingers. “Have you ever wondered about getting out? I mean all of us—you, Sophronia, and me. Just leaving it all behind.”

“Hannah, please. Don’t speak of it. That’s apostasy. It isn’t safe.”

She pressed her lips together to keep them from trembling. “Don’t you see?” she said after a moment of studying him. “We shouldn’t have to worry about speaking our minds.” She reached up and touched his jaw, stroking it gently. “Lucas, we shouldn’t have to worry about following the Church’s orders—you following your mission, me obediently keeping up appearances—before we can be married.” She paused, pulling back and looking him straight in the eyes. “And what would you do if an apostle, an elder, or even the Prophet himself, declined to let us wed … or wanted me for his own? What would you do? Would your devotion to the Church be stronger than our love?”

Lucas met her troubled gaze with an intensity of emotion that seemed to pull her heart and soul into his safekeeping. There was such caring in his face, such unspoken love, that Hannah caught her breath. “The Church will bless our union; you must believe that, Hannah. I cant tell you any more than that, but please believe it. They aren’t out to destroy us. They will bless us on th

e day we wed.”

“The day we wed?” Hannah searched his face. “Wed? Us?”

Lucas smiled, then added. “But, Hannah, you can’t say a word to anyone. I wasn’t supposed to tell.”

“Oh, Lucas!” Hannah cried and circled her arms around his neck.

Grinning, he kissed her once on the tip of her nose then fully on her lips. “My darling,” he murmured, “will you wait for my return?” His expression told her he already knew her answer.

“I’ve waited since the day I met you,” she declared. “I’ll wait forever to be yours if I have to.” Then with a deep and contented sigh, Hannah laid her head on Lucas’s chest, relishing the warmth of his rough woolen vest against her cheek. “Oh, Lucas,” she murmured. “Just promise you’ll come back to me soon.”

“A thousand wild, stampeding horses couldn’t keep me away,” he said, pulling her into a tender embrace.

An hour later, Lucas, with John Steele and Porter Roe at his side, watched Brother Hambelton kneel beside a freshly dug grave, his face buried in his hands. Snatches of mumbled, sobbing utterances filled the midnight silence.

When John Steele finished entreating the Lord’s blessing on the atonement, Hambelton looked up and nodded. Then the young man fixed his gaze far into the midnight darkness. His face was grim, but he held himself steady.

“Brother Hambelton, do you understand that you are giving your life in order to save it eternally?” John Steele’s voice was gentle yet filled with godly authority.

The young man nodded, still not meeting their eyes.

“It is an honorable thing you are doing, Brother—to willingly shed your blood for remission of your sins.”

Brother Hambelton nodded again, slowly. “Just do it, brothers,” he whispered raggedly. “Just be done with it, I beg you.”

“As you wish, Brother.” John Steele pulled a knife from a sheath at his belt and moved quickly toward the kneeling man.

Angels Undercover

Angels Undercover The Sister Wife

The Sister Wife The Betrayal

The Betrayal The Missing Ingredient

The Missing Ingredient Come, My Little Angel

Come, My Little Angel The Butterfly Farm

The Butterfly Farm The Master’s Hand

The Master’s Hand Heart of Glass

Heart of Glass Through the Fire

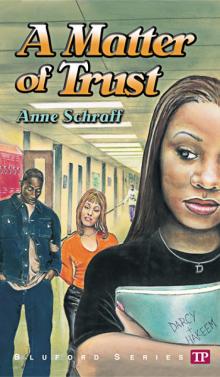

Through the Fire A Matter of Trust

A Matter of Trust The Veil

The Veil The Curious Case of the Missing Figurehead: A Novel (A Professor and Mrs. Littlefield Mystery)

The Curious Case of the Missing Figurehead: A Novel (A Professor and Mrs. Littlefield Mystery)