- Home

- Diane Noble

The Veil Page 26

The Veil Read online

Page 26

Minutes later, the two men mounted and kicked their horses to a trot. They joined the other riders—Silas Edwards, the Mitchell boys, the Prewitt brothers, Hampton and Billy Farrington, and Jesse O’Donnell—just outside the circle, and as the sun slipped beneath the horizon and an ashen dusk settled heavily onto the land, the company rode east.

It was well past dark by the time Alexander returned. An unnatural quiet had fallen over the normally lively company. Tonight there was no music or dancing, no laughter or singing. The word about the Missouri Wildcats had spread among the travelers, and a few groups of husbands and wives huddled together, speaking in hushed tones.

Something told Ellie that part of their discussion included criticism of Alexander. Every day she overheard talk about his leadership causing them to run late.

Alexander sat down heavily and pulled his chair to the table. Ellie spooned the stew into his bowl then sliced a wedge of cornbread. “What happened?” she asked, arranging the dishes before him on the table. She could see the worry on his face and figured she already knew the answer. “Did they agree to leave us alone?”

He shook his head as Ellie placed a fork and knife next to the bowl of stew. “No,” he said, lifting his fork to take a bite of stew. “They’re not of a mind to listen. We’ve warned them, though, to stay a good distance behind. We really can’t do much more than that.”

“Maybe they’ll tire of trailing behind,” Ellie said hopefully. “Their herd won’t find much grass left for grazing once ours has moved through.”

“I mentioned that fact to them, El,” Alexander said. “They’re stubborn. They’ve got it in mind that they’re safer with us. Once we’re west of Independence Rock, we may have Indian trouble ourselves.”

“There haven’t been attacks for years, Alexander. You said so yourself. I didn’t think it was much of a worry.”

“Not from attacks on the company—but on the horses and cattle. Nearly every company coming through here loses hundreds.” He took another bite of stew then cut a second piece of cornbread.

“They won’t be content to stay a few miles behind, then, will they, Alexander?” Ellie settled into the chair across from him at the little table.

“No,” he said with a heavy sigh. “No, if it’s safety they’re looking for, they’re going to get as close to us as they can.”

The air was heavy. No hint of a breeze broke the feeling of sticky heat that had settled over the night camp. Alexander looked up at the sky. Even the stars were obscured by the moisture in the air. “I think tomorrow we may get our rain,” he said.

“There’s something else bothering you, Alexander.” Ellie reached for his hand.

He smiled into her eyes. “You’ve always known me too well, Ellie.”

“And you’ve always tried to protect me too well, Captain Farrington,” she said with a small smile. “What is it?”

“There’s another reason the Missouri Wildcats want our protection.” He let his hand rest beside the bowl of stew.

“It’s because of Utah, isn’t it?” she asked.

He nodded slowly. “They’ve guessed correctly that we have no other choice but to take the Mormon road to the Old Spanish Trail and head across the desert into southern California.”

Ellie moved her gaze to the fire’s dying embers. “And the Wildcats think the Mormons are to be feared?”

He nodded again, still not finishing his stew. “They say the Mormons have a secret army called the Danites. They kill in the name of the Church. In the name of God.”

“I have a hard time believing that, Alexander. It sounds to me like this group is simply trying to convince you there’s a reason to stay together.”

“I hope that’s true,” he said, once again picking up his fork and taking another bite of buffalo.

“I think our greatest worry,” she said softly, “comes not from the Missouri Wildcats but from people in our company. There’s talk about electing a new captain.”

“I know, Ellie. I’ve heard. But its only talk.”

“There are those who say they’ll leave the train if we head through Utah Territory,” Ellie said.

“Then maybe they’ll have to do just that,” Alexander said, his face grim. “I can’t make them stay with us. I can only point out their folly in crossing the Sierras this late.”

“Then we’ll be a smaller group than before,” Ellie said. “A more defenseless company, followed by thugs and ruffians.”

“Yes,” Alexander said, staring at the dying fire. “But we won’t know any of this as a certainty until we reach Fort Bridger.”

“Suddenly, I’m afraid,” she whispered. “Alexander, I’m so afraid.”

He reached across the table and took her hands in his, then lifting them to his lips, he kissed them gently. His gray eyes met hers as if unable to release her gaze. She could see Alexander understood her fear. He didn’t make light of it or tell her to ignore it. Instead, he gazed into Ellie’s eyes, silently affirming a love that would never die, a love that would live on no matter what lay ahead.

Around them, most of the families were now in bed, and those still awake began putting out their oil lamps.

Soon the only light remaining in the night circle was from the dying embers of the dung cook fires. Smoke hung heavy in the air, and there was not a hint of a breeze to push it away.

TWENTY

Lucas reined Spitfire to a halt at the summit of Big Mountain. Through the pass before him spread his first far-off view of the Great Salt Lake. The sun was setting behind a high pile of clouds, casting crimson-and-purple shadows across the valley of the Saints.

For days he’d ridden the stallion hard, making good time along the trail—through Emigrant’s Gap, Devil’s Gate, South Pass along the Sweetwater, Fort Bridger—and finally into the Wasatch Mountains. The climb ahead would be difficult: through the southern end of East Canyon, up and over Little Mountain, and through Emigration Canyon, the last one before the valley itself. He planned to wait until morning to attempt it; the moon wasn’t yet full enough for night riding, and Spitfire needed the rest.

He put the horse out to graze near a wooded spring, gathered some twigs, and started a small cook fire. He’d shot a small rabbit earlier in the afternoon, and now he proceeded to gut and skin it and skewer it for roasting. Pounding a couple of forked twigs into the ground on either side of the fire, he then set the rabbit in place. Soon it sizzled and popped as the juices splattered into the flames.

As he tended the rabbit, his thoughts turned to the difficult days he knew lay ahead. With each hour of his travels since leaving the Farrington train, he’d had a growing sense of trepidation. Now that he’d almost reached the valley, it was clearer to him than ever: He had but one mission, and that was to see Hannah and Sophronia safely out of the territory, no matter the cost. He would sacrifice his own life, if necessary.

He wondered why it had taken him so long to see the bitter truth of their circumstances. Through the years he’d been lulled into believing that the Saints were his only family, his protectors, his champions. And after what he’d seen done to his mother and father and baby brother by the Gentiles, he’d distrusted all people outside the valley, outside the confines of the Church.

Yet something, perhaps Someone, was drawing him away. Even his aborted mission to England had served to show him that there existed another truth worth considering. Perhaps it was because he’d spent hours alone on the trail, away from the doctrine preached by the Prophet, his elders and apostles, away from people who spoke the same words, repeated the same phrases they’d heard in services the Sunday before.

This mission had been Lucas’s first alone, without the company of elders and bishops and apostles. And he’d relished the lack of intrusion into his innermost thoughts.

He turned the rabbit to brown on its other side and drew in a deep breath. Around him dusk had fallen, and the night music of the woods began to play, the voices of owls, the whistles of bats, the sawing of cric

kets’ legs, now and then the soft whinny of Spitfire still grazing near the bubbling spring.

He thought about his chance meeting with the Farrington train, his talks with Alexander and Ellie. Especially Ellie. The entire encounter had served to pull away some covering that had blinded him for nearly all his life. Since his conversation with Ellie the night before he left the train, thoughts about God had been pouring into his heart and soul, thoughts he couldn’t ignore. And he had pondered them as he rode, pondered a God different than he’d known before.

A God of love, not vengeance. A singular God, all-knowing, all-powerful, full of grace and glory. A God who had existed from everlasting to everlasting.

Lucas knew that such a God existed. He wasn’t sure how he knew. He just did, feeling its certainty clear through to his soul.

But one thought still pierced his heart. He had committed brutal crimes on behalf of the Church. He hadn’t actually held the knife when an apostate’s throat was being slit. He hadn’t actually held the knife when a young man was mutilated for not giving up his betrothed to an elder who wanted to marry her. But he’d been present during dozens of atrocities carried out in the name of God.

And he had done nothing. He had remained silent. And he knew his intimidating presence as a Danite, an Avenging Angel, kept the victims in check as surely as if Lucas had bound them with ropes. He knew he was just as guilty for the crimes as if he’d wielded the knife himself. Crimes against the innocent. Crimes against men who had been questioning the truth given to them by the Saints—just as he himself was now questioning. One by one their faces came to mind, and he heard their cries for mercy, their screams of pain. And he saw his face turning away from theirs, ashamed at what he’d witnessed.

Lucas stared into the fire, unable to bear the darkness inside him.

After a moment, he absently turned the rabbit again, and its juices splattered and smoked. In the distance a screech owl screamed, then was answered by another, farther away. A breeze kicked up, rustling the leaves and shifting the cook fire’s ashes, sending sparks into the air.

How could God forgive him? Lucas couldn’t even forgive himself. How could this God he was just beginning to understand accept a man so filled with darkness? He smiled grimly to himself. Maybe the Saints were right. It was easier to believe you could achieve God’s favor through your own efforts, obedience, and good works. It was easier than considering the chasm between the darkness in a man’s heart and the holiness of God.

He considered the Saints’ recent teaching of blood atonement. Could it be possible that there were sins—such as his—that couldn’t be forgiven in any other way except through the shedding of blood? Even the ancient Hebrews believed in the atonement of sins through blood sacrifice, though it was that of an unblemished lamb.

Lucas stood, making his way through a stand of aspen toward the spring to check on Spitfire. The stallion nuzzled his palm, and he patted the animal on its neck, feeling the velvet smoothness of its hide. Then, stooping near the water, swift moving and clear, Lucas scooped up a handful and drank of its sweetness.

It is not sacrifice I require, my beloved.

It is your heart.

Lucas looked up through the surrounding trees into the blackness of the night sky. A light breeze rustled the quaking aspen, carrying the fragrance of the roasting meat in a mix of fresh, pine-scented air and wood smoke. He bent to drink again from the stream.

The sacrifice has been made, my child.

It was I who was wounded, so that you might be healed.

Lucas slept restlessly that night; a dark and troubled awareness of his return to the Salt Lake valley kept pressing into his mind. Several times he awoke with a start only to fall again into a fitful sleep. Finally, an hour before dawn, he rose, saddled the stallion, and packed his gear. Before the first rays of sun spilled through the aspen, he kicked the horse to a trot along the winding trail that led down Big Mountain. Lucas rode Spitfire hard all day, camped that night at the mouth of Emigration Canyon, then late the following evening reined the stallion to a halt at the corral near his cabin.

The next day was Sunday, and Lucas—clean-shaven, bathed, and in fresh clothes for the first time in weeks—rode into town. He felt better than he had in days, and his anticipation of seeing Hannah mounted with Spitfires every step.

He turned toward the meetinghouse a few minutes before the services were scheduled to begin, dismounted, and secured the stallions reins to a hitching post. He figured he’d surprise Hannah and Sophie by his presence during the services as well as put in a needed appearance. He didn’t want to alarm the Prophet, John Steele, or any of the others, and he planned to play out his role as a Saint in the highest standing until he could get the women safely transported from the territory.

Porter Roe, still sporting a full beard and a mane of stringy hair, was standing at the entrance. “Lucas!” he cried, striding down the stairs two at a time to meet him. “We weren’t expecting you for some time. What’s happened?” They shook hands as his piercing gaze flicked across Lucas’s face.

“I’ve got news for Brother Brigham,” Lucas said. “Got as far as Kearney before turning back. It was too important to ignore.”

“When’d you get in?”

“Last night, late.”

“And if your news came from Kearney,” Roe began with a frown, “you might as well have continued on your mission. Your news is about Johnston’s army?”

“So Brigham’s already aware of it.”

“I delivered the message myself. I was in Illinois when I heard about the troop movement. Hightailed it back here as fast as I could.”

They were standing in front of the meetinghouse now. A few people milled about, some calling out greetings to Lucas, others making their way inside to be seated.

“I didn’t know you were heading east last time I saw you,” Lucas said. “You were here in the valley the night before I left.” Images of Brother Hambleton’s killing flashed through Lucas’s mind. He briefly wondered if Roe had been ordered to follow him. “How was it you ended up in Illinois?”

Roe gave him a hard look but didn’t respond to the question. “I was in Springfield June twelfth,” he said simply. “Heard Senator Stephen Douglas make a speech. He said he had it on good authority that we Mormons are not loyal to the U.S. government.” Porter lifted a brow sagaciously. “He charged that nine out of ten of Utah’s inhabitants are aliens, that Mormons are bound to their leader by ‘horrid oaths,’ that the Church is inciting Indians to acts of hostility, and that the Danites, or Destroying Angels, as he called us, are robbing and killing American citizens.”

Lucas couldn’t help laughing. “Well, brother, I’d say he’s right, wouldn’t you?”

Roe gave him another piercing stare before continuing. “There was another speech, one I didn’t hear, a few weeks later. It was reported by one of our brothers who stayed behind in Springfield after I left. It was given by Abraham Lincoln, who said that Utah’s territorial status should be repealed and that we should be placed under the judicial control of neighboring states. He said, ‘The Mormons ought to be called into obedience.’”

“That’s when President Buchanan stepped in and issued the order to attack,” Lucas added.

Roe nodded. “Buchanan responded by calling the ‘Mormon problem’ one of civil disobedience. And soon after, General Scott dispatched the orders to Fort Leavenworth, instructing Johnston to outfit a detachment of twenty-six hundred men and officers for garrison service in Utah—specifically to restore order and support civil authority—no matter the cost.”

“What’s been the response here?”

This time Roe laughed. “You should’ve been here for Brigham’s Independence Day sermon on the twenty-fourth of July. We had the usual gathering of hundreds of families from all over the territory—north and south. Celebration’s been going on for a couple of weeks now. Fact is, most of the families are just now starting to leave.” He looked toward the meeting room. �

�Standing room only inside. Today’s the last day of the celebration.”

Lucas knew all about the Saints’ Independence Day. He and Hannah and Sophie had usually celebrated it together—starting on the anniversary of the day that the Saints had first entered the Salt Lake valley. Folks camped in parks around the city, sang and danced and thanked God for their blessings … and their blessed Zion, their Promised Land.

If the Prophet ever needed to get news to the whole territory about Church edicts or revelations, it was always a good time to present them. Lucas could only imagine the fiery speeches—by Brigham Young himself, his council, and his apostles.

Roe let his assessing gaze again flick across Lucas’s face. “Not only the Prophet, but everyone who spoke told our people how they need to prepare for war. Our enemies will be overcome, Brother Knight, have no doubt about that.”

“I have no doubt,” Lucas agreed, wondering if Roe had reason to doubt his sincerity.

“I thought not,” Roe said. “According to Brother Kimball, our enemies shall be annihilated before they reach Big Mountain. He said, And we shall have manna!”‘ Roe chuckled. “Which, of course, was looking at the bright side of the situation. But when you think about it, it’s true. The U.S. government has seven hundred supply wagons heading our way. They’re also bringing seven thousand head of cattle.” He smiled. “Just suppose, Brother Knight, that the troops don’t get here but all those goods and cattle do.”

Lucas nodded. The Saints were always shrewd, turning the advantage their direction. “Manna from heaven,” he agreed.

“The United States is sending troops to make desolation of our people,” Roe said, his voice rising in passion. “We do not intend to let that happen. Brigham told our people to arm themselves—men and women alike. We will fight to the death. Every one of us.”

Lucas frowned. “I thought you said the troops were ordered to Utah to restore civil obedience … not to make desolation of the Saints.”

Angels Undercover

Angels Undercover The Sister Wife

The Sister Wife The Betrayal

The Betrayal The Missing Ingredient

The Missing Ingredient Come, My Little Angel

Come, My Little Angel The Butterfly Farm

The Butterfly Farm The Master’s Hand

The Master’s Hand Heart of Glass

Heart of Glass Through the Fire

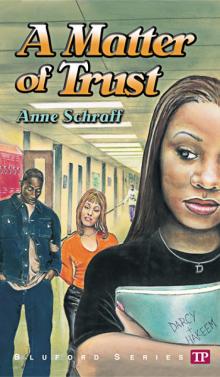

Through the Fire A Matter of Trust

A Matter of Trust The Veil

The Veil The Curious Case of the Missing Figurehead: A Novel (A Professor and Mrs. Littlefield Mystery)

The Curious Case of the Missing Figurehead: A Novel (A Professor and Mrs. Littlefield Mystery)