- Home

- Diane Noble

The Veil Page 3

The Veil Read online

Page 3

Ellie knelt beside Alexander, and she reached for the little girl’s hands.

“Wherever we go,” she said, “it’s God who will be leading us. Just like a shepherd takes care of his flock, he’s leading us. And he’s holding you—just like he holds his little lambs—in his arms. The Holy Bible tells us he’s holding you and all your brothers and sisters near his heart. That’s what makes us feel at home, no matter where we are.”

Amanda Roseanne suddenly giggled. “Hampton’s nearly as big as a horse. And Billy too. God’s holdin’ them like lambs?”

Alexander laughed. “They’re both healthy, strapping boys, but they’re still in need of God’s leading. The same is true for you—even after you’re as big as that pony over there.” She followed his gaze and giggled again.

Ellie stood, and the little girl took her hand. “Miss Ellie,” she said, her face tilted upward. “Can I be in the weddin’?”

She gently touched the child’s cheek. “I was hoping you’d want to be,” she said. “You and your sisters too.”

“I want to hold your veil,” Amanda Roseanne said, her face now all smiles, “and throw posies.” She danced about happily. “And I want to call you Ma.”

“I’d like nothing better,” said Ellie.

Alexander’s loving gaze met Ellie’s, and she smiled into his eyes. “Shall we go home to tell the others about the wedding?” he asked.

“Yes,” Ellie said, her joy so deep she could scarcely breathe. “Let’s do.”

“But I want to tell Hampton and Billie and everyone about goin’ west,” said Amanda Roseanne. “I want to be the one to tell about that.” She seemed to have forgotten that the trek west might be years away.

“Then tell you will!” said Alexander, taking his daughter’s hand.

The sun had now slipped behind darkening clouds, and a light snow was falling. Alexander and Ellie, with little Amanda Roseanne dancing between them, walked toward the waiting horses. Ellie shivered in the cold.

ONE

Wolf Pen Creek, Kentucky

September 1846

Ten-year-old Hannah McClary crept along the trace leading from the creek to the crest of Pine Mountain. Farther on, the trail wound into the lavender hills, through the pass, and far beyond where the eye could see, to Kentucky’s tall silver grass country.

With every step Hannah looked for evidence that her brother Mattie had taken this path when he disappeared. She stopped, brushed her hair back from her face, and inspected the broken twig of a mountain laurel, turning it in her fingers. He’d gone looking for some old Daniel Boone trail, she was sure. Hannah figured her brother left Indian signs for her to follow, just as he had done in play when she was but a wee tike.

Hannah examined the bent twig for shreds of buckskin, perhaps caught as Mattie hurried by. But there were none. She frowned, turning the tender shoot in her hand. It was a recent break, maybe caused by a lone Cherokee hunter, or maybe by Mattie. She moved farther up the trace, deeper into the dark forest of birches, oaks, hickories, and maples.

Her brother had always said he would take her with him when he left—that was the part about his leaving that saddened her the most. Her other six siblings were mostly sullen, like their pa, or unnaturally quiet. Since their ma died, only Mattie seemed to have the same curiosity for life that Hannah had. He was her protector, her champion, just like knights of old they read about in the primers and fairy-tale books some distant cousin had sent from Virginia. And he told her stories he’d heard from their Irish grandma’am. Stories about God and his care for them all. Mattie said he knew for certain that Hannah was someone special in the eyes of her Creator.

Mattie had taught himself to read and write, then he’d taught Hannah as well, opening a world of notions and longings to them both. The rest of the family, with the exception of their ma, couldn’t be bothered with book-learning. The others mocked them, calling Mattie and Hannah dreamers, scoffing at the very word.

But now Mattie had left without Hannah, without a hint telling her where he was going. And every day when her chores were done, Hannah searched for his trail, thinking surely he meant for her to follow.

Today, as usual, there was no sign of Mattie, and Hannah let out a short sigh of frustration. Little Shepherd Creek lay just over the hill, and she hurried through the thick rhododendron bushes to reach it, flopping down on her stomach when she did and splashing its cool, clear water on her hot face.

Hannah squinted at her reflection as she scooped up a swallow of water and gulped it down. One time Mattie had told her that, although she should be careful of vainglory, her eyes were like some bright Indian stones he’d seen once at a trading post. The thought of such a hue, of course, had pleased Hannah hugely. But now, looking into the rippling water, she could see nothing except the hint of a sad and somewhat curious expression. The creek water was too dark to see the freckles that Mattie always teased her about or the wild curls that he told her were exactly the color of sunlight on wheat.

It was Mattie who had called her Fae, saying the name was better suited for such a sprite as she. When Hannah asked what a fae was, he just smiled and said it was a cross between a fairy and an angel, only a bit different, since any faes around there were wee Kentucky mountain folk and strong as oxen. Mattie was the only one to call her by that name. She wished she could hear him say it now.

Still lying on her stomach staring into the creek, Hannah rested her chin in her palms, thinking of all she missed about her brother. The scent of decaying leaves and damp earth filled her nostrils. She preferred that scent to any other she could think of, from wild lilacs to baking bread. The only scent that came close was a sprinkle of rain on a warm, summer day.

As she lay there, Hannah was struck by a thought she couldn’t put from her mind. What if she followed this trail to its end, looking for her brother? Mattie himself had told her about the Cherokee trading post just to the west of Pine Mountain. If she could follow the trace up the mountain beside Little Shepherd Creek, she hoped it would lead her to the outpost. After all, it was an Indian trail from centuries ago. Once there, she was certain someone would tell her if Mattie had traveled through. The thoughts tumbled through her mind, growing until she finally concluded that it was exactly what she needed to do.

Feeling immensely better, Hannah sat up and wiped her hands on her homespun skirt. Of course, she’d need provisions, and that would take some planning. Victuals for days, perhaps weeks, of traveling. She would make pemmican out of berries, cornmeal, and lard, just like Mattie had said the Indians made. And she would borrow Pa’s rifle. That might take some doing, because she knew how upset Pa would be when he found it missing. She didn’t like to consider that he would miss his rifle more than he would miss her, but she knew it to be true.

A few years earlier, Pa had taught the older boys to shoot. Hannah, knowing better than to ask Pa to teach her too, had badgered Mattie into setting up a target at the top of the hollow, out of earshot of the house, and teaching Hannah everything he knew about the old mountain-man rifle. She had learned to load the powder, place the ball, and ram it down the barrel, and soon she could outshoot the rest of the boys.

Hannah headed back down the trace toward the house at Wolf Pen Creek, skipping and humming as she went. With all Mattie had taught her about survival in these mountains, she knew she could find her brother. Of course, that was figuring Mattie wanted to be found.

Barely two weeks later, Angus McClary hauled his defiant runaway daughter back down the trace from where he had found her hiding in a clump of sweet-smelling rhododendron at the crest of Pine Mountain.

“I was just looking for Mattie,” she wailed.

Angus tightened his grip on her shoulder. “I’ll not put up with you one day longer,” he muttered. Clomping noisily down the trail behind their father, Hannah’s six brothers snickered in agreement.

She clamped her lips together, determined to keep her dismay to herself. Her first attempt to follow Mattie had fai

led, but that did not mean she would not try again. She would just be smarter next time. She lifted her chin, staring dead ahead as her father pulled her rapidly along the trail.

As soon as they reached the house, Angus dismissed the boys so he could talk to his daughter alone. Bees droning in the background were more pleasant to Hannah than the mean sound of her fathers voice as he laid out his plan. A cottontail hopped from behind a clump of ferns, and the family’s big yellow dog barked sharply, sending the little animal skittering out of sight.

“I’ll have no argument from you,” he told her. “You have no say in this. You’re going to Sophronia’s.”

“Who’s Sophronia?”

“Your mother’s aunt.”

“But I don’t know her,” she said. “How can you send me to someone I don’t even know?”

Her brothers, who were now lolling on the porch, howled with delight at the word of her coming departure. Hannah didn’t give them the satisfaction of acknowledging their hoots and hollers.

“Why?” she asked again. By now there was a knot in her stomach.

“This here is no place for a girl,” Angus finally admitted, his voice unnaturally gruff. “And Sophronia is the only one I can think of who might be willin’ to take you in.”

Hannah swallowed hard. It was one thing to run away trying to find Mattie. It was another to be sent away from home as if she were no more useful to the family than some old worn-out pack mule. Hannah didn’t cry easily, but her father’s words caused a sting in the back of her eyes.

“You’re set on sending me away to this … this stranger?” she finally managed.

“It’s a sight better than marrying you off, Hannah Grace,” her father said. Behind him, the boys guffawed.

Hannah looked up at her pa. But he didn’t meet her eyes. He was still holding the rifle, rubbing the barrel carefully with his shirt-tail.

Hannah tried again. “But, Pa—” she began. “You can’t really mean it. You don’t mean for me to go … do you?”

Her father’s face seemed to soften for an instant, then immediately became hard set again. “I mean it with every bone in my body, child,” he said. “It’s high time you left these hills.”

“But what about Mattie? What if I’m gone when he comes back? What if I miss him?” she cried, hardly able to bear the thought. “What then?” Her father knew nothing of the kinship deeper than blood that ran between them, and she knew her words fell on a hardened heart.

“He ain’t never comin’ back,” one of her brothers taunted from the porch. “He’s still a-lookin’ fer ol’ Dan’l.” The other boys joined in the gruff laughter. “And he’s got a lot of country to cover before he finds ol’ Dan Boone,” one of the others added. “‘Specially since Dan’l died some years ago.”

Hannah ignored them. “I know he meant for me to follow him. I just know it. Please, don’t send me to Sophronia. Just let me try one more time to find Mattie. Please, Pa?”

“You quit your whining, Hannah,” her father demanded. “You’ll do as I say. You forget Mattie. You run away again, you’ll just get yourself caught by Indians. You’re lucky we found you before they did. We’ll leave first thing in the morning. And I don’t want to hear any back talk.”

“Tomorrow?” That definitely would not give her time to try once more to find Mattie. “At least let’s wait till the end of the week. Or maybe till after harvest. You’ll need help with the corn. I’m always a big help. You’ve said so yourself.”

“We leave tomorrow for Illinois. And that’s that!” her pa said as he turned to walk toward the porch full of boys.

“Illinois?” Hannah whispered, looking up at her pa. That was a long way off. She’d seen it on a map.

“That’s the last place I heard your great-aunt Sophronia was living.”

Great-aunt Sophronia. Hannah drew in a deep sigh of resignation, trying to imagine life with some tottering ancient woman who could do nothing more than sit in a rocking chair, covered by a lap robe.

Her gaze moved to the distant Kentucky hills with their cloak of pines, birches, oaks, and maples, soon to turn flame red and burnished gold. Then she focused on the late-summer wildflowers scattered among the pale meadow grasses. She would be gone by the time the blossoms were spent; she would be forgotten by the time spring brought new life.

She blinked back her tears and watched as her pa entered the house and slammed the door behind him. “All right,” she finally muttered to herself. “Tomorrow.”

Barely a month later, Angus McClary, with Hannah at his side, drove the buckboard through the thriving town of Nauvoo, Illinois. They stopped only once, to ask the whereabouts of Sophronia Shannon. A smiling, apple-cheeked woman in a poke bonnet pointed out the way, and within the hour, Angus clucked the horses to the top of a rise near the river.

He reined the horses onto a winding dirt road that led through a wide picket gate to a modest two-story house painted gray and white. A friendly looking place, Hannah had to admit, set right in the middle of a countryside filled with breathtaking beauty. The house was framed by a great stretch of grassland, dotted by apple trees heavy with bright red fruit. Wildflowers bloomed in patches of yellow and purple across the summer green pasture that was crisscrossed with trails winding into the woods beyond. A small wood-slatted barn stood just beyond the house, and two horses grazed in a corral to its side.

Angus halted the horses, but before they could step from the wagon a white-haired woman opened the door, gave them a quizzical look, then moved toward them with a surprisingly spry gait.

Great-aunt Sophronia was anything but what Hannah had imagined. This was no shriveled old woman sitting under a lap blanket. Instead, Sophronia seemed to glow like the evening star. She had wild, curly hair that she didn’t bother to tie down. Hannah’s had the same unruly curl, but whereas Hannah’s was the color of the morning sun, Sophronia’s was white as fresh-fallen snow. Her skin was tanned, and her eyes were the color of a purple sky, with squint lines that turned up as if from decades of pleasing thoughts. She was tall and broad shouldered, her big hands callous like a man’s.

Sophronia held Hannah by the shoulders with her wide hands, looking her up and down. “You’re a fine work. A fine work.” Then she smiled and hugged her close. “My, it’s going to be good to have young blood in the household again,” she said after the circumstances had been explained.

“It’s female manners she needs, Sophie.” Angus was standing behind Hannah. “Growin up with a house full of brothers and no ma, she’s turned out more boy than girl. Hannah needs some settling. I figured bein here, close to town and all, you could see to it she gets the best life has to offer.”

Hannah was stunned. It was the first time she had considered her pa might be sending her away for her own good, not simply getting her out from under foot or keeping her from running off with his rifle.

Then Hannah noticed that Sophronia didn’t seem to be paying any attention whatsoever to Angus’s words. Instead, the older woman had fixed her gaze on Hannah and was studying her with a look of admiration. Hannah smiled, feeling something deep inside unfold the same way a blossom opened to the sun, and she basked unabashedly in the love and warmth she found there.

She barely noticed when her pa prepared to leave for Wolf Pen Creek the following morning. She was too busy listening to Sophronia tell how she’d seen Mattie. He’d been by to visit her twice in Nauvoo and had promised to come back for a third visit sometime soon.

“Of course,” she laughed, as Hannah’s pa headed the buckboard back down the road. “Soon to our Mattie might be years from now.”

Hannah couldn’t stop asking questions about her brother. Though Sophronia had no answers for most of them, Hannah held close the knowledge that Mattie had been seen and that he was alive and well.

“And I declare, I think he’s happy!” Sophronia added as if reading her thoughts. “The boy’s a natural wanderer, and though last he said he was heading south because he’d met a girl

he planned to woo, I have no doubt he’ll return someday. Maybe with his new bride.”

“Did he say if she’s pretty?”

“Pretty as a picture,” Sophronia said, and Hannah sighed with happiness.

“What’s her name?”

“He called her his sweet Mandy.”

“I always wanted a sister. Maybe Mandy will be the one.”

The first week of Hannah’s stay, Sophronia said she wanted to hear all about the girl’s life in Kentucky. She listened attentively as they worked side by side in the garden, tilling the soil around the autumn crop of squash and gourds. Hannah hadn’t had anyone so interested in her words since Mattie, and she talked nonstop, answering all of her aunt’s questions and asking hundreds of her own.

They rode Sophronia’s mares, Berry and Foxfire, along the rusty-red trails, the elderly woman surprising the girl with her spirited yet gentle way with horses. She taught Hannah to brush and comb Foxfire, the horse she said was now Hannah’s own, and Hannah learned to clean out the stalls and pitch fresh hay from the loft.

By the end of the third week, the first frost of winter covered the flat, bleak land, and Sophronia taught her niece the art of laying a fire in the fireplace, keeping the coals hot so the fire would last all day long.

In the dark of late afternoon they often sat near the large stone fireplace in Sophronia’s front living room, the older woman in a tapestry-covered rocker, her yarn basket at her side, Hannah in a slender oak rocker, scarred from years of use. Bookcases lined the rough-hewn walls, and framed prints that appeared to be from some faraway country like England, Scotland, or maybe Ireland, Hannah thought, were scattered around the entire room. An oak secretary fit squarely against the wall opposite the fireplace, a pewter lamp glowing from its gleaming top. A worn horsehair sofa with two well-used overstuffed chairs completed the sitting area around the fire, a flat trunk with an embroidered lace doily serving as a tabletop. Two large windows draped with Irish lace flanked the heavy door leading to a wide front porch with its sweeping view of the fenced pasture and the small woods beyond the barn.

Angels Undercover

Angels Undercover The Sister Wife

The Sister Wife The Betrayal

The Betrayal The Missing Ingredient

The Missing Ingredient Come, My Little Angel

Come, My Little Angel The Butterfly Farm

The Butterfly Farm The Master’s Hand

The Master’s Hand Heart of Glass

Heart of Glass Through the Fire

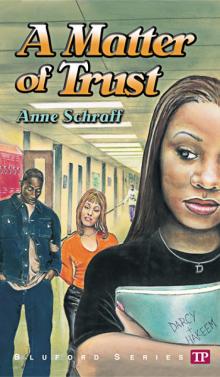

Through the Fire A Matter of Trust

A Matter of Trust The Veil

The Veil The Curious Case of the Missing Figurehead: A Novel (A Professor and Mrs. Littlefield Mystery)

The Curious Case of the Missing Figurehead: A Novel (A Professor and Mrs. Littlefield Mystery)